We built Zedge Premium with one main goal: to make it easier to make a living making art.

The Zedge app gives artists access to a global audience of over 30 million people seeking wallpapers, live wallpapers and ringtones they can use to personalize their mobile phones; if you’re an artist, Zedge Premium’s toolset lets you choose if and how to earn money by offering your creations to all those people. You can give some of your work away for free, you can put some or all of your items behind ad gates, and/or you can choose to charge any price you desire for different pieces of art. Since our users can unlock your items by watching ads or by redeeming Zedge Credits they can earn for free within the app, you earn money even when a particular buyer feels like he or she’s getting your work without spending a dime.

Importantly, though, we do not judge what qualifies as art: while you must apply to Zedge Premium and prove the works you upload are yours, we never reject anyone based on our own subjective opinions about the quality of that work – if you made something, and someone else might want that thing, you’re welcome here.

That openness is a critical part of both our philosophy and our business strategy. It’s also surprisingly controversial, among some of our artists as well as a few of my colleagues at Zedge. And I confess that sometimes, looking at the number of items in Zedge Premium that have simply been copy-and-pasted from royalty-free stock photo sites, or generated by AI engines that still can’t manage to spell “Happy New Year” or “St. Patrick’s Day” correctly, a small part of me wonders if those colleagues might be right, and if actual artists, Zedge’s user base, and Zedge as a business wouldn’t all be better served by us taking a much stricter, more curated approach.

But those moments are fleeting, because I witnessed the power of an open marketplace a decade and a half ago, when I was helping build Google Play. Unlike Apple’s App Store, which was highly curated and made it quite difficult to get an app or game approved unless it followed a lot of very strict (and sometimes inexplicable) rules, Google Play made it quite easy for most any developer to launch a new app or game. The downside was that meant our store was filled with a lot of crappy (and occasionally malicious) apps. It was worth it, though, because that freedom also gave those developers an opportunity to experiment and innovate in a way Apple’s platform actively discouraged.

The example I always use to illustrate this phenomenon is Angry Birds, a mobile game that you had to pay to download from the App Store in 2009, but which Rovio, its developer, experimented by offering for free on Android. Before they knew it, they were making more money from the freemium versions than they ever had with the paid ones.

The results were both fast and profound: in 2010, most of the games in the Android Market (the precursor to Google Play) were paid; by the time I left in 2014, the entire mobile gaming industry had done a 180 on their business model, and the vast majority of mobile games cost nothing to install – yet they were making hundreds of millions of dollars. That kind of evolution never would have happened with a more curated marketplace.

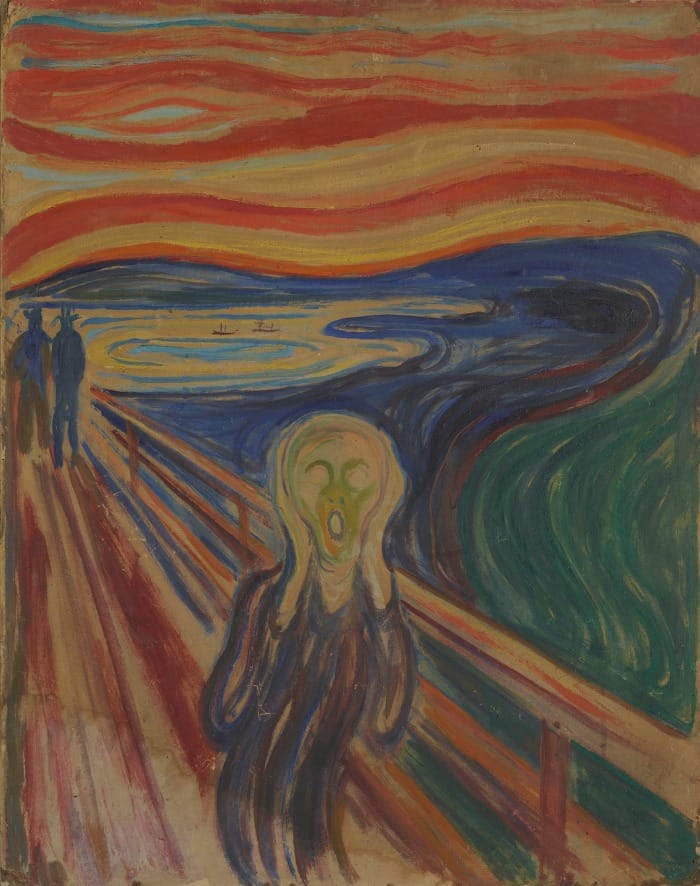

That’s the strategic reason behind Zedge Premium’s openness: we know that taking a very light curatorial approach will lead our artists to innovate in ways our product managers and devs would probably never have dreamed up on our own. The philosophical reasons are just as powerful, though: history’s full of examples of artists whose work was first reviled, but is regarded now as genius. Since Zedge was founded in Norway, let’s point to that country’s Edvard Munch: his 1892 exhibition in Berlin led to such outrage it was forcibly closed in a matter of days, but he’s now one of the few painters who’s a household name across the planet. The Scream, his most famous work, pretty much sums up the entire 20th century (even though he painted it in 1893 – that’s how ahead of their time true artists often are).

I used the phrase “true artist” above advisedly. The thing about true artists is that you often can’t recognize them until after the fact. As much as I cringe at some of what I personally consider the less accomplished work offered in Zedge Premium, I cringe more at the thought of ever being one of the smug, short-sighted gatekeepers who turned down this century’s Munch.

Our job at Zedge isn’t to pick and choose who’s a potential Munch and who’s not – that’s a task that can only be accomplished by time and the audience. Our job is merely to create systems that make it as easy as possible for anybody who installs our app to find their personal Munch.